One of the upsides of having our own place in France will be the ability to travel back and forth with minimal baggage because (hopefully) we’ll have most of what we need in both places. Clothing is easy, I have a large-ish wardrobe, and I tend to buy multiples of things I like.

What is thornier is stuff related to my hobbies. For me that means mainly four areas: bicycles, musical instruments, cameras, and tools for my carving/woodworking. This class of possessions (I’m repeating the George Carlin routine about “stuff” in my head and trying hard to avoid the word!) seems especially important since we can’t legally work in France. For my sanity, and Carolyn’s, I will need to keep myself busy; when I go too long without making things, or riding a bike, or playing guitar, I notice the dip in my mood and quality of life.

Guitars: I have nice guitars. I love them. I play them every day—most were made in one-person shops by people I consider to be friends. The guitars would be difficult if not impossible to replace. I purchased a hardshell flight case for the acoustic guitar I thought I’d leave in France, but I’m still nervous about bringing the guitar to Europe.

With the flight case, I’m less concerned about damage during transit and more concerned about confiscation of my guitar under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) regulations or the US Lacey act. Either law would allow officials to seize a guitar if they had reasonable suspicion that it contains protected/prohibited materials such as Brazilian rosewood, tortoise shell, mother of pearl from protected clam species, or ivory. None of my guitars contain those materials, but the burden of proof would be on me if I was questioned, and the small, one-person shops that build these guitars don’t have the means to generate the documentation proving compliance with CITES/Lacey. There’s a personal exemption in CITES that I don’t fully understand. Maybe, I’ll just buy a new guitar there?

Bicycles: This one isn’t really a problem. I have a touring bike that’s designed to break down and pack into two standard size suitcases. The bike was made by Rivendell and I had Bilenky add S&S couplers in 2008 after Air France charged me €250 to bring the bike back from Paris. There had been no charge to fly out of the US with the bike, and despite a business class ticket that entitled me to check sporting equipment for free, the guy at the Charles de Gaulle check in counter invited me to leave my bike behind in Paris if I didn’t want to pay the fee. I don’t ride this bike often in Texas and I won’t miss it here if it lives in France (in Austin, I mostly ride the cargo bike with our dog, Woody).

I’m researching options for a cargo bike in France so that Woody and I can continue exploring together in the future. I can’t wait to take him to the beach!

Cameras: I have finally surrendered to the fact that I don’t get emotionally invested in digital photography in the same way I do with film photography. I need the physical artifact—there’s something about looking at a negative and holding an actual print in one’s hands that makes it more real. Don’t get me wrong. I love the camera on my phone and digital cameras are fun, but they feel inherently unserious to me, as though they are only good for making work that is quickly consumed and quickly forgotten. That’s my hang up, of course. I’m sure the old 8x10 view camera guys felt the same way about medium format and 35mm photography when those inventions came along.

Traveling with film is not easy. Even thirteen years ago, going through Japan’s airports with film was an exercise in diplomacy. Several times I ran into young inspectors who had never seen film before. In the pre-9/11 world, a film-safe bag and friendly security staff gave your film a chance of surviving, but all the new scanning technology and high-stakes security environment make it impractical to travel with unexposed film. TSA agents I encounter are either completely joyless or completely fed up with our nonsense. I’d hate to ask them to hand inspect anything and even if they agree (they probably would) I’m not sure what the rules allow in French airports. Fortunately, I located two small camera stores in Montpellier, so I expect to be able to buy film without difficulty.

Speaking of difficulty, let’s talk about knives . . .

Carving tools: I would love to bring a small hatchet, a variety of gouges, and a few spoon knives with blades bent into sexy arcs and compound curves, and maybe a slöjd knife or two. Can you imagine what that’s going to look like on the airport security scan!? They’ll definitely be opening my bag.

(Carolyn wants to interrupt here to ask the reader how long a wife is required to wait around while her husband is detained by customs before she jumps in a cab and waits for him at the local bar.)

My research into the laws around knives in France didn’t turn up anything definitive regarding travel into the country. It is illegal to carry a pocket knife (or anything that could be used as a weapon) in France whether you are in the city or the countryside. Most sources say the rule is “lightly enforced.” Not comforting. The law differentiates between owning and carrying—you aren’t allowed to carry a knife (some sources add “without a legitimate reason”)—but you are allowed to own them in your home. I don’t plan to carry my knives around, but I do need to get through customs and transport them from the airport to our house. I worry the tools and sharpening stones make it look like I’m trying to work in France.

I mainly work with green wood these days, carving spoons and shrink pots and other small useful objects. I am looking forward to finding local sources for green wood and discovering what species of trees are easily available in the area.

Some of my nervousness about the tools has to do with a scary experience I had in Singapore. While working in Borneo in 2010, I took a brief trip out of the country to reset my visa which included a weekend layover in Singapore. I needed to clear customs before I could spend a few days sleeping in a good bed, taking hot showers, and enjoying Singapore’s excellent food and drink. I was carrying all the supplies I needed for life in West Kalimantan, including a folding survival knife with a short, thick, very sharp blade. As I made my way through the Singapore airport, I arrived at the customs declaration area with the usual two lines: Nothing to Declare and the other, slower moving line, Something to Declare.

Where the line split into nothing/something there was a huge sign (with pictures!) labeled PROHIBITED ITEMS. The list included nunchucks, switchblades, guns, swords, bullwhips, blackjacks, brass knuckles, and more—it was a long, very specific list. There was nothing like my knife on the list (I read it twice, carefully) so I headed towards the fast-moving Nothing to Declare line and put my bag onto the conveyor belt. After a long flight, I was dreaming of the Mandarin Oriental where a lap pool, a spectacular breakfast buffet, and the New York Times waited for me. I wasn’t trying to hide the knife—it was nestled in with my tee shirts, plain as day. In a scan, I had no doubt they’d see it. I just didn’t think they’d care.

Of course they cared. As my bag exited the scanner and tumbled down the chute, a crisply groomed guy in a uniform picked it up, pulled me aside, and asked me to open the bag (he was very polite and professional). He felt around in the open bag, quickly pulled out the knife, and asked me why I didn’t declare it. I gestured towards the big list with the pictures and pointed out that there wasn’t a similar knife on the list. “We can’t list every little thing.” he said, exasperated. “Follow me, please.”

We walked through a rabbit warren of sterile, windowless hallways to his office. “Please sit, wait here.” I sat. About 30 minutes later a different uniformed guy came in and asked me why I was carrying the knife. I told him about the work I was doing in Indonesia building a low-resource hospital at the edge of a jungle. I explained that I used the knife every day for cooking, working, fishing, and fixing things.

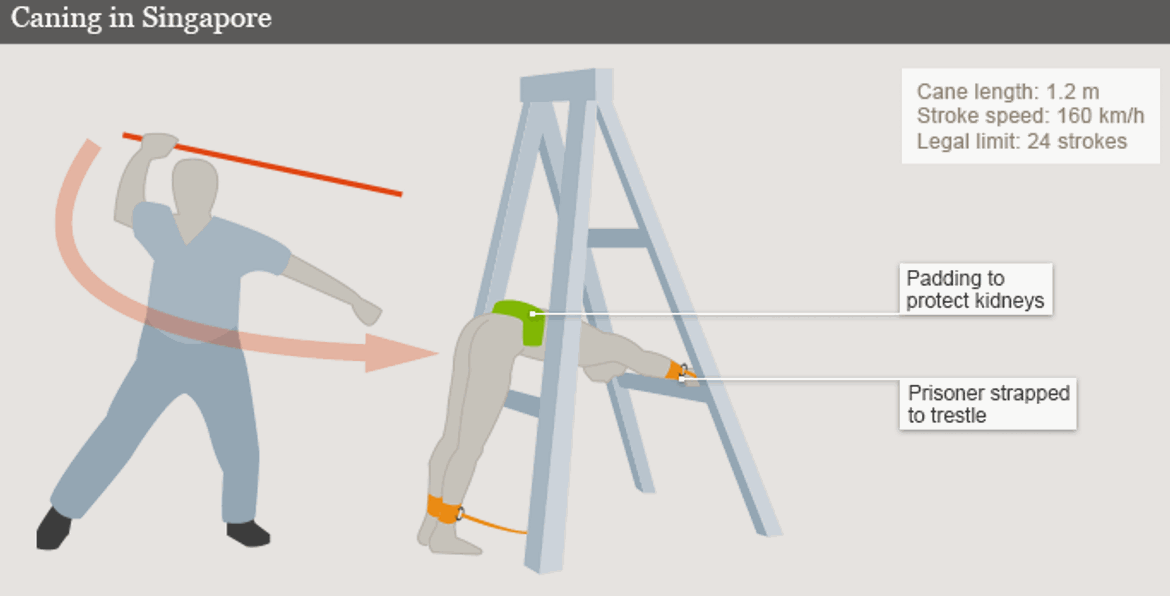

“Okay. Thank you.” He took some notes, then left again for another half hour. He returned carrying a small stack of papers. It was a confession for me to sign. I immediately thought of that American kid, Michael Fay, who got caned for chewing gum or stealing traffic signs or something. He later claimed to have signed a false confession on the promise that he wouldn’t be caned if he confessed. He was CANED.

A sentence at the bottom of my confession informed me that Singapore was choosing not to prosecute me for my crime at this time, and warned me that if I ever committed any other crime in Singapore, no matter how small, I would be prosecuted for that crime and for this crime as well.

That weekend, I don’t think I went anywhere that required me to even cross the street. I was terrified I was going to jay walk or spit in the grass and end up in jail waiting for a professional level ass-whipping.

Like an idiot, I asked, “So will I get the knife back?” I didn’t mean right then. I thought maybe they could give it to me on my way out of the country (on account of all the good I was trying to do in the world, y’all!) The guy in the uniform actually laughed out loud before he said no and escorted me out of the airport all the way to the taxi line.

So yeah—I’m now a little nervous about crossing borders with knives (or small axes).

In conclusion, this is a whole load of nervousness about “stuff.” But it’s really about me needing to learn new rules in new places and adjust to new customs. I support the CITES regulations—I want governments to protect endangered species and I want luthiers to work with sustainable, cruelty-free materials. I’m grateful for enhanced security measures that make international travel safer for everyone. As a Texan who finds it preposterous that people can walk around with pistols strapped to their hip, I’m happy that the French have more sensible laws about carrying weapons in public.

None of these concerns diminish my excitement for travel and new adventures. I cannot wait for us to get back to Montpellier, and I’ll keep you updated on how the conveyance of “stuff” unfolds.

Jusqu’à la prochaine fois (until next time),

Carolyn & Roberto

Roberto here. I keep staring at that caning diagram, first it makes me shudder, then I think, "that yoga instructor is really serious about getting downward dog right!"

Leave all blade's at home. I'm happy to hold on to some for you, in the meantime & I totally would have stayed home too.