We all know the clichés about French snobbery around their language and their quickness to correct your mistakes, but do you know about the Académie Française?

The French literary academy was established by the French first minister Cardinal Richelieu in 1634 . . . It has existed, except for an interruption during the era of the French Revolution, to the present day . . . The original purpose of the French Academy was to maintain standards of literary taste and to establish the literary language. Its membership is limited to 40.

The Academy has included many acclaimed authors such as Voltaire, Victor Hugo and Eugène Ionesco. I love this quote from the Académie’s former chairman, Maurice Druon:

How do we implement our mission? By revising, several pages of the Dictionnaire every week; accepting or rejecting, often by a vote, words newly introduced; by updating definitions, recording new meanings, and indicating the register of language. We also issue cautions, warnings and statements, and judgments. We do our best to induce a sense of sin in those who maltreat the French language. And when we reach the letter Z we start again, like Penelope at her weaving. A new edition of the Dictionnaire appears at intervals of 30 to 50 years.

“A sense of sin!” Too good.

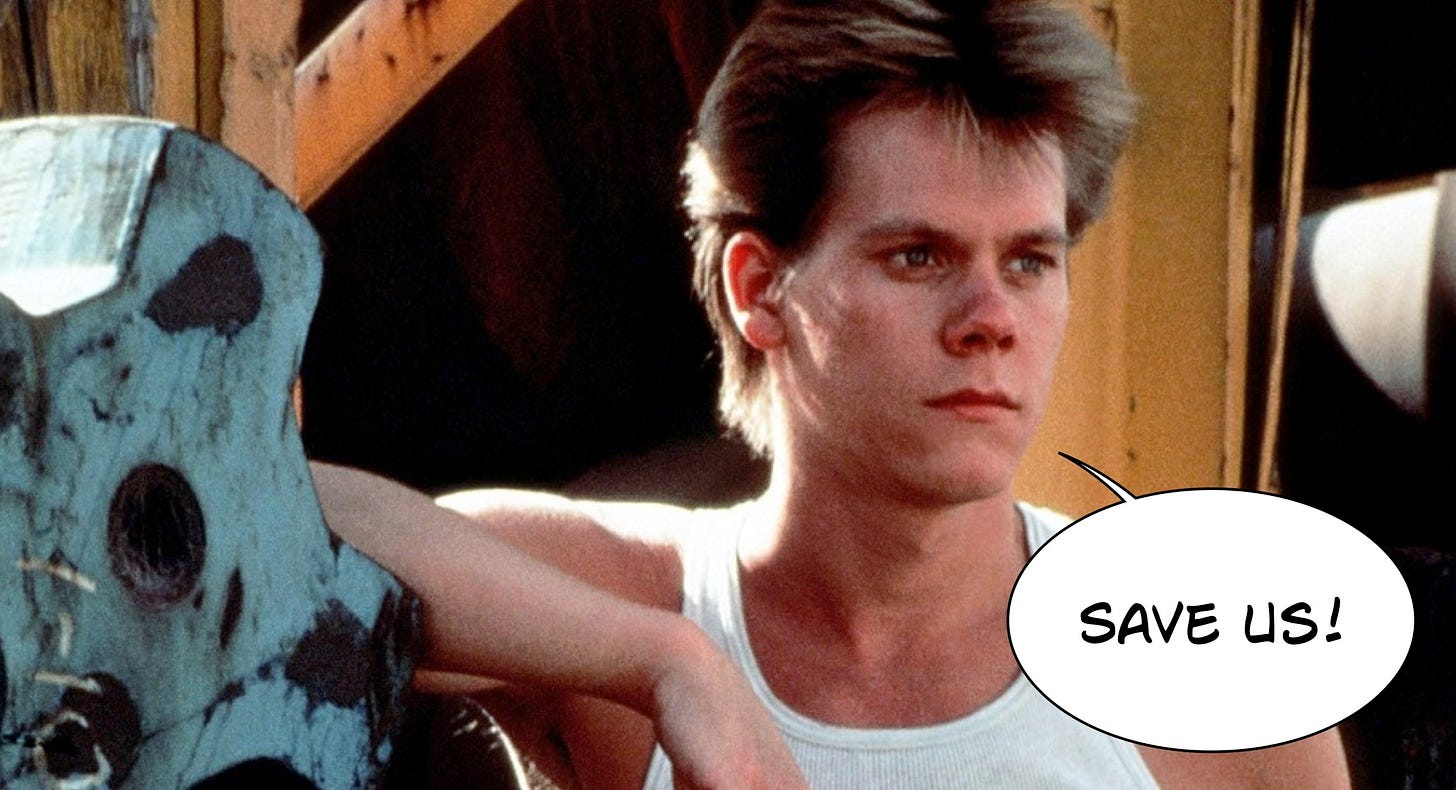

They will decide if certain anglophone terms are acceptable, such as le wokisme, la success story, or my favorite, le burn out. Yes, I am referring to the Académie Française as “they” and not “it” because I imagine the organization is a group of very stern Frenchmen who still look like this:

Okay. I posted that image as a joke and then Googled the actual group and got this photo from 2003!

They also get to decide when language is being used improperly, such as their 2014 declaration that people should stop overusing du coup, which literally means “suddenly” or “therefore,” but is peppered throughout conversations by young people in the same gratuitous way in which Americans use “like.” (I have seen some very entertaining attempts to banish “like” from children’s speech—the most successful attempt was a teacher who gave each student a jar of Skittles and each time they said “like” she took one out. At the end of the week, students could eat whatever was left in their jar.)

Imagine if our government banned the use of “like?” Imagine if our government cared about language at all? (or people or education for that matter). Now imagine if the government got to weigh in on your baby’s name. In this article from The Local, the writer explains:

Up until 1993 parents in France had to choose a name for their baby from a long list of acceptable prénoms laid out by authorities. But the list was scrapped under President François Mitterand and French parents were given the liberty to be a little bit more inventive.

1993?? I felt like this was surely a typo and they meant 1893. But no. Up until the early 90s French parents had to choose from a list of names that includes all the cliché French names that you know: Pierre, Jacques, Olivier, Jean-Pierre, many other Jean-somethings, etc. (now you know why they are cliché). They were all considered good Christian names when the law was created by Napoleon, a pretty chill guy whose ideas should definitely be propagated until the late 20th century.

After the naming law was banished, many parents were delighted to name their children after popular characters and celebrities of the 90s, leading to a batch of names like Kevin (from Home Alone, Beverly Hills 90210, and Dances With Wolves) and Cindy (as in Lauper and Crawford).

These names were seen as “quirky” and by the time these children grew up, their names had become a sign of social class. Previously popular names trickled down from the upper classes, but these new ones were coming from the working class. There is so much of a stigma against the name Kevin that “some 2,700 French Kevins apply for a name change every year.”

In 2015, the Observatoire des Discriminations, a research institute monitoring social exclusion, found that job applicants named Kevin were between 10 and 30% less likely to be hired than someone called Arthur, despite having equivalent qualifications and experience. Other Kevins have talked openly about the class contempt experienced because of their name.

The situation is so bad that one Kevin is making a documentary about it. The film titled Sauvons les Kevin (Let’s Save the Kevins), is described as a film “about Kevins, with Kevins and by a Kevin.” He wants to “restore the dignity of the Kevinosphere.”

Was your whole high school a Kevinosphere? I know mine was.

Americans can’t feign shock. Many studies have been done about job discrimination in the USA when a name is perceived to be African American. And look what we have done to the name Karen!

The naming law is gone, however when you register your baby’s name with a civil servant they can report you to the Procureur de la République (public prosecutor) if they think the child will suffer from your choice. If this sounds archaic take a look at some of these names that were banned ban because the judge thought would have “an adverse effect on the little one's life.”

Clitorine and Vagina

Nutella and Fraise (Strawberry)

Jihad

Mini-Cooper

Prince-William

Anal (Bwahaha.)

Poor French celebrities! How are they supposed to name their children Apple, Brooklyn, RZA, Moon Unit, or X?

To conclude, I am going to share some of my favorite American phrases that have been French-ified and added to the lexicon (I cannot guarantee they have been approved by the Académie Française, so use them at your own peril).

Bruncher. To eat brunch

Tweeter. To tweet.

Forwarder. To forward an email

Liker. To like an update or posting, typically on Facebook

Skyper. To Skype with someone. I assume there must be a Zoomer as well.

Le relooking. In reference to a makeover

Please share any of your own favorites in the comments section.

Jusqu’á la prochain fois (until next time),

Carolyn & Roberto

This was enlightening AND humorous, exactly the sort of thing I like to read. Free the Kevins!

When our son was born in France, a midwife came into my hospital room with a pen and a piece of paper and asked me to write his name *very carefully*. She explained she was taking it directly to the Mairie to be registered, and that there could be no mistakes.

It felt sort of charming and old-school at the time, but I later learned it was actually a relatively recent reform (from 2005!) meant to correct a long-standing imbalance: it used to be that whichever parent showed up at the Mairie first had the legal right to name the baby. Since moms were typically still recovering in the hospital, this gave dads a clear naming advantage.

Now both parents have to agree in writing (and spelling really matters) because correcting an error on the "acte de naissance" is a bureaucratic nightmare I wouldn’t wish on anyone.

Anyway, more grist for the French naming mill! Thanks for this delightful post.